Note: I’m not a doctor, nor do I play one on TV. The post below is presented for informational purposes only. See your physician for medical advice.

For many people, this week marks the return to “normal life” after the holidays: back to work, back to school, back to whatever you were doing on a regular basis before the holiday season swept us away. I laughed along with friends who posted videos on Facebook of people weeping at the prospect of taking off their pajamas for the first time in a couple of weeks, children struggling to wake up early for school. And at the same time, I was a little uncomfortable laughing at someone’s distress –because I know that, for some people, depression didn’t start when the holidays ended and won’t ease up once they get back into the swing of things. For some people, depression is anything but a joke.

As a culture, we’ve come a long way in our understanding of depression as a form of mental illness. My mom struggled with clinical depression all her life, though she wasn’t properly diagnosed (because doctors didn’t really understand what depression was, or how to treat it) until she was in her 60’s. She was very open about her struggle, though, and that’s why I’m going to share part of her story today: she understood that no good would come of hiding her diagnosis and that talking about her illness actually made it possible for others  to do the same. Her example helped me to be open about depression with my own kids. Like alcoholism, diabetes, and a host of other medical conditions, depression tends to run through the generations in families that are predisposed to it. When my daughter was diagnosed with depression last fall, that happened because she recognized the symptoms and took charge of her health by seeking out the appropriate medical help.

to do the same. Her example helped me to be open about depression with my own kids. Like alcoholism, diabetes, and a host of other medical conditions, depression tends to run through the generations in families that are predisposed to it. When my daughter was diagnosed with depression last fall, that happened because she recognized the symptoms and took charge of her health by seeking out the appropriate medical help.

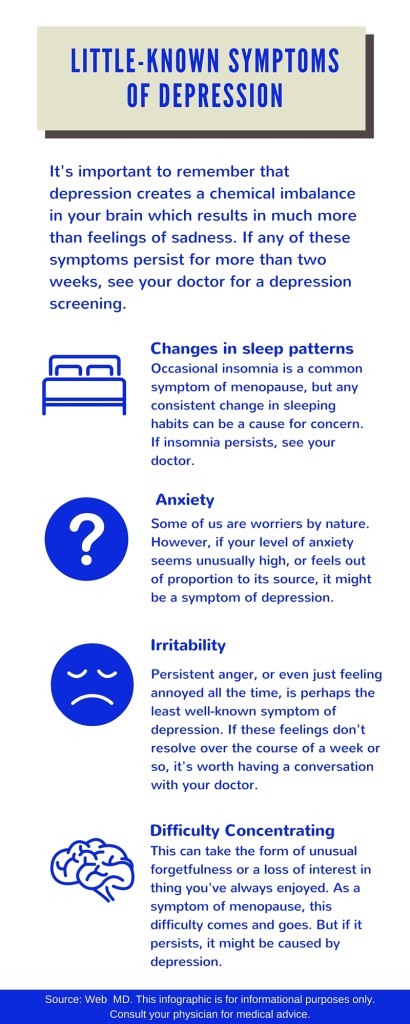

Still, for all the progress we’ve made, many people misunderstand depression: they still think of it as “being depressed,” or feeling sad. When my mom was suffering through her first major depressive episode–before she was hospitalized for the first time–many of her friends advised her to “get outside and go for a walk,” or “make a batch of cookies,” or “focus on God, not the devil.” The problem with all of this advice is that depression actually depresses everything in your body–your motivation to do anything, your interest in any activity, even those you’ve thoroughly enjoyed in the past. And depression has absolutely nothing to do with sin or redemption. Telling a depressed person to “focus on God” suggests that their illness is their own moral failing. If that were true, of course, then anti-depressant medications would be of no help, and those meds have been the saving grace of many people who find themselves in the grip of this insidious mental illness.

Depression does, sometimes, involve feelings of sorrow, but it’s much more complex than that. Depression affects chemical levels in the brain, which in turn affect the brain’s operation. Since the brain is the powerhouse of the body, it shouldn’t be so hard to understand that when the brain isn’t working the way it should, neither is anything else. Someone suffering from depression often has severe stomach pain, for instance, though a trip to the doctor will reveal no obvious reason for it. That doesn’t mean the pain isn’t real. Its cause is simply in another part of the body, one that isn’t being examined. Refusing to believe someone who complains of physical pain is, not surprisingly, an excellent way to exacerbate depression and make that person feel even more isolated.

Another little-known symptom of depression is irrational anger and irritability. When I think of my mom during my childhood, it seems as if she was always annoyed or angry about something. She was never abusive, but all my memories of her being happy or playful come from a later point in her life, after I’d had children of my own. As a kid, all I really understood about this was that my mom wasn’t like my friends’ moms. She didn’t like to have other children at our house, and there were a million ways to set her off, so I learned early on to just stay out of her way. Both my brother and I played at our friends’ houses, or outdoors, as often as we could. And, as a result of that, my relationship with my mom took place mostly at a distance throughout our lives, because we really didn’t know each other. Depression had made that impossible.

Now, as an adult looking back on my mother’s life, I wonder how it was even possible for her to hold herself together through sheer force of will. She rarely slept. She worried about everything. And still, my mom survived the difficult early years of her marriage, isolated in a country where she didn’t speak the language; she survived the loss of her first child, my sister Debbie, who died of cancer over the course of a year and passed away at just seven years old. My mom got through those things without the aid of anti-depressants or even psychological counseling, and I have no idea how. My understanding of her strength grows every time I think about these things.

But let me be very clear about something: it’s dangerous to think of depression as something you can just struggle through. In my extended family, there’s also a history of suicide–and thwarted suicide attempts–that tells the story of what happens when you treat depression as something you can ignore until it goes away or becomes more manageable, because sometimes it doesn’t. Even my mother, who’d found a way to be strong for so many years, attempted to take her life before she was properly diagnosed and medicated. (Again, this is something she was very open about, so I don’t feel as if I’m telling tales out of school by discussing it here.) If you, or someone you know, is exhibiting symptoms of depression, and those symptoms don’t resolve over the course of two weeks, seeing a doctor is your best course of action.

And sometimes, taking medication to treat depression isn’t necessary; there are many ways to hold minor depression at bay, and these strategies work for many people. I try to be strict about sleep and exercise for precisely this reason, in the hope that I can avoid taking anti-depressants. However, I know it’s possible that I might end up needing them anyway, and I’m always very clear about this when I see a new doctor. Depression is part of my family medical history, just like heart disease and diabetes. The fact that depression sets up shop in your brain, not your pancreas, doesn’t make it any less real or dangerous, or any more controllable. And the fact that some people can manage their depression without medication doesn’t necessarily mean that you can, too.

One of the things I hear over and over again is that depression is just attention-seeking behavior. In fact, I once told a friend about my mom’s history and was met with the question “Do you think she wanted to kill herself, or was she just trying to get attention?” Well, if she was trying to get attention–why not? If you’d been hit by a car and needed help, wouldn’t you try to get someone’s attention in the hope that they would get you the medical assistance you couldn’t seek out yourself? Depression takes away the ability to exercise self-care. That’s why those of us who see someone struggling often need to step in, just exactly as we would in any medical emergency.

If you love someone who’s exhibiting any of the symptoms I’ve mentioned here, and if those symptoms persist for two weeks or more, please encourage them to talk to a doctor. And if you are dealing with these symptoms, please take care of yourself before depression removes your ability to do that. You, and the people who love you, will be so happy that you did.

4 Comments

Thanks for sharing some important thoughts. I deal with foreign teens who are studying in the U.S. for a semester or academic year. They’re often “just” homesick, or sad/depressed on a short-term basis. I put that in quotes because sometimes the reaction we get from a host family or someone who doesn’t know the student well is that “they should just get over it.” Yet homesickness and short-term situational depression can turn into something more serious before you know it. We’re sort of trained to keep an eye out for more serious symptoms, but it’s hard, especially with teens who are less likely to share how they’re really feeling.

This is such an important topic to bring to the forefront and discuss. I have a family member who suffers from severe depression, and there is still such a stigma attached to it. Thanks for sharing your story.

Thanks for sharing information on such an important topic that plagues so many. It’s something that’s very personal for me too.

Important topic to discuss. Being aware of these symptoms is very important and helpful in identifying depression earlier, and hopefully doing something about it before making changes gets really difficult as a result of more severe depression.