Many years ago, I remember reading Roger Ebert’s review of the movie Wonder Boys. I remember that review mostly because it’s the only one I know of that states a very simple fact: on university campuses, students come and go. Professors stay. In addition to being an environment where those students can grow, develop, and move on, the campus is also a workplace. That’s easy to forget.

Because I spent many years working in retail, I’m always conscious of the fact that when I’m shopping, I’m part of somebody’s work day. But that’s not the same as being at work myself. When I’m shopping, I rarely pay attention to the information broadcast on the PA system. Even if I do, what I usually hear is people speaking in code. And, of course, I don’t know the employees personally–who gets along, who had an argument in the break room ten minutes ago. I know the front stage, not the back stage.

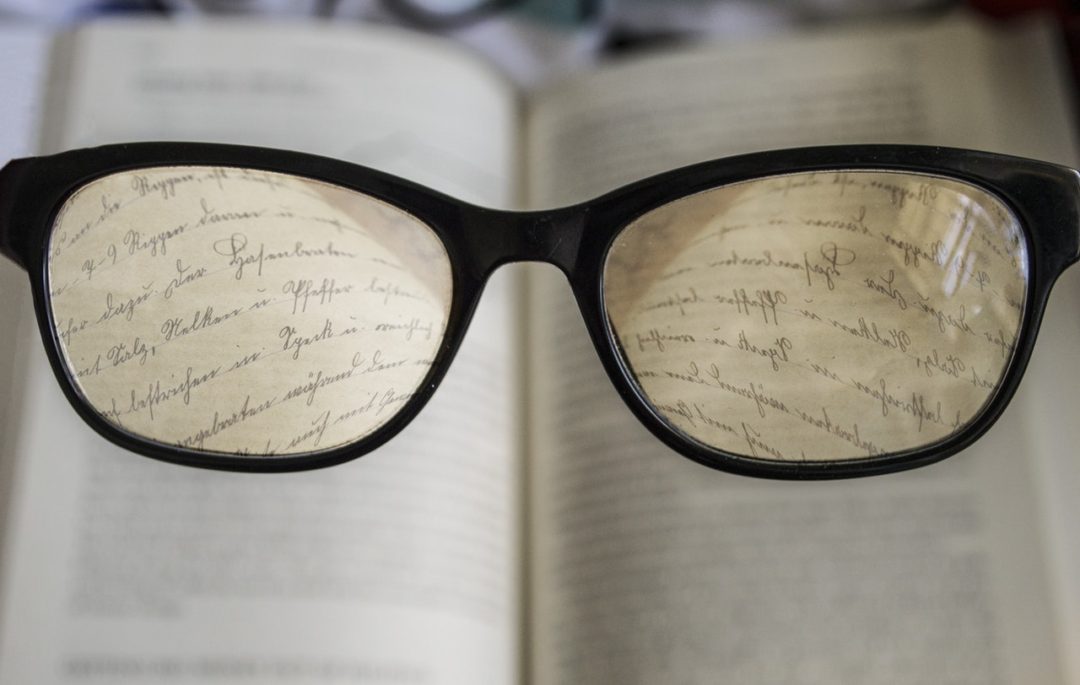

The same is true of a university campus. We have our own codes: tenured, not tenured, Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, adjunct faculty, visiting professor. Most people don’t understand the differences between these ranks; there’s really no reason why they should. And don’t even get me started on the acronyms: QEP, SACS, the alphabet soup of committee names.

Then there’s the backstory. New students don’t know which professors were married for 25 years before they divorced last spring. They don’t know who’s native to the area and who’s trying to make sense of this strange place. Returning students don’t know why Professor X suddenly isn’t on campus anymore. (Or, if they do, they know the version of that story Professor X decided to share.) Just like me when I’m at Target, they see only the front stage.

And that’s exactly why, although I enjoy my job most of the time, I bristle a little when someone says I think I’d like to be a professor. Anyone who hasn’t taken a peek behind the curtain is basing that statement on a front stage understanding of my job.

So let’s pull back that curtain just a bit. Here’s a short (and by no means exhaustive) list of things a professor has likely done long before you met them in a college classroom.

- Taken many graduate classes, every single one of which required extensive reading, writing, and research.

- Earned an A in every one of those classes. (In graduate school, anything less than A work is simply unacceptable.)

- Lived below the poverty line while earning a small stipend for teaching (or taking out student loans.) Alternatively, a part-time graduate student might be working a full-time day job.

- Taught the basic courses that many students resent having to take. (In English, this often means first-year composition.) Serving as a graduate instructor is an important part of training new professors to do their jobs. But we’re teaching these courses in a country where the absence of graduate instructors is used as a selling point by small colleges, which doesn’t improve students’ attitude toward the graduate instructors they encounter.

- If a professor teaches in a Humanities discipline, it’s also likely they were required to study one or two foreign languages.

Having pulled back the curtain just this far, many graduate students flee academia for good. But for those of us who stick it out and have the good fortune to find a job, here’s one real day in the life. (Different disciplines have different requirements, of course, so our days vary widely.)

- Arrive on campus before my first class with enough time to look over my notes and get my brain in the right place for leading a clear but challenging discussion.

- Use the half hour between my first and second classes to do the same thing, but point my brain in a completely different direction.

- Talk to the colleagues who have arrived for the day while I was in class. Discuss a problem; suggest a potential solution; realize this solution will create new problems. Agree to keep thinking.

- Check email. Respond to student concerns, but leave everything else for later.

- Oops. 12:30. Almost class time again. Prepare for yet another class on yet another topic while shoving some food into my mouth.

- Teach another class.

- Finally done with classes. Time for a committee meeting.

- Come back to my office. Consider whether to do the work generated by the committee meeting, take care of email, start grading papers, or prepare for class tomorrow.

- Figure that I’ll just be distracted by committee work and email if I don’t do those first. While writing an email, think of two others that need to be written.

- Remember that I’m chairing a committee meeting tomorrow. Check the agenda for that meeting and send an email to the committee.

- Respond to replies to the emails I’ve sent out in the last hour. Remember that I still need to deal with the email from this morning.

- Decide class prep for tomorrow can wait and get ready to start grading. Then realize it’s late afternoon and I have two choices: leave now, to beat rush hour traffic, or miss dinner with my family.

- Get home. Make dinner. Talk to my family.

- Grade papers all evening, since I didn’t get to them this afternoon.

- Plan to get up early enough to arrive on campus in time to prepare for class in the morning.

A few scenes that didn’t appear in my day: spending a long, leisurely afternoon reading literature. Hanging out under a tree with my students, reading poetry aloud. Doing any writing of my own. (Other than email, of course.) Much more likely would be the scene where I’m writing to the Dean of Students about someone who has stopped coming to class. Or the scene where I’m writing an email to that student, offering my help.

Those are the scenes you’ll never see in a movie about a professor who’s just doing the best she can.

No Comments